Many diseases are driven by proteins that are difficult or impossible to inhibit with conventional drugs. Instead of blocking their activity, an emerging therapeutic strategy aims to remove these proteins entirely from the cell by harnessing the cell’s own degradation machinery. In a new study, researchers at CeMM, AITHYRA and the Scripps Research Institute have now developed a systematic method to discover such protein-degrading compounds on a large scale. The approach, published in Nature Chemical Biology (DOI: 10.1038/s41589-025-02137-2) provides a powerful new route toward therapies for diseases such as certain aggressive forms of leukemia.

Cells constantly monitor and recycle their proteins through a tightly regulated waste-disposal system. Proteins that are no longer needed are tagged and broken down by specialized cellular machinery. Recent advances in drug discovery seek to exploit this system by redirecting it toward disease-relevant targets.

This strategy relies on so-called molecular glues, small molecules that induce interactions between proteins that would not normally bind to each other. If a disease-causing protein can be brought into contact with a cellular degradation enzyme, it is selectively eliminated by the cell itself.

Until now, however, most molecular glues have been discovered by chance, limiting their broader therapeutic application.

Large-scale chemistry meets cell-based screening

The new method developed by the teams of Georg Winter (Scientific Director at the AITHYRA Research Institute for Biomedical Artificial Intelligence and Adjunct Principal Investigator at the CeMM Research Center for Molecular Medicine in Vienna, Austria) and Michael Erb (Associate Professor at the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California, U.S.A.). addresses this limitation. Starting from a small molecule that already binds to a target protein, the researchers generated thousands of chemical variants by systematically attaching different molecular building blocks. Each variant subtly reshapes the surface of the protein, potentially enabling new protein–protein interactions.

Crucially, these compounds were screened directly in living cells, without prior purification, using a sensitive assay that reports whether the target protein is being degraded. This enabled rapid identification of active compounds from a vast chemical space.

“Our approach combines high-throughput chemistry with functional testing in cells,” says Miquel Muñoz i Ordoño, co-first author of the study and PhD Student in Georg Winter’s lab. “This allows us to explore chemical diversity at a scale that was previously impractical, while immediately seeing which compounds have a desired biological effect.”

A selective degrader for a leukemia-associated protein

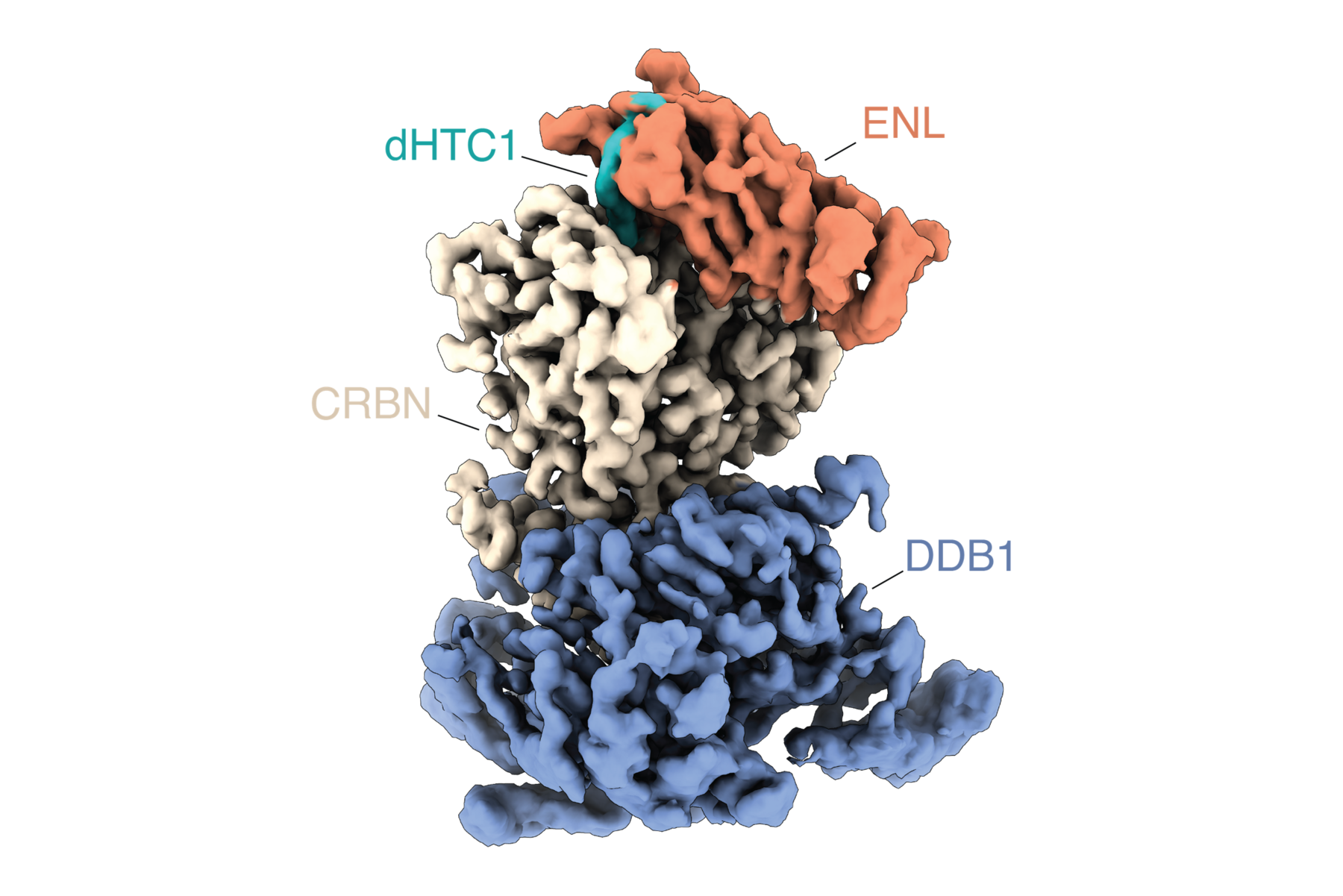

As a proof of principle, the researchers focused on ENL, a protein that plays a central role in certain forms of acute leukemia. From several thousand tested compounds, the team identified a molecule that efficiently and selectively triggers degradation of ENL in leukemia cells.

Further analyses showed that the compound primarily affects ENL and downstream gene programs controlled by this protein, leading to a strong reduction in the growth of ENL-dependent leukemia cells. They also revealed that the compound acts through a cooperative mechanism characteristic of molecular glues. Rather than binding strongly to all interaction partners, it first binds ENL and then creates a new interaction surface that recruits a cellular ubiquitin ligase, which marks ENL for degradation.

“This cooperative mode of action is what makes molecular glues both powerful and selective,” explains Winter. “The compound only becomes active in the right molecular context, which helps limit unwanted effects.”

Systematic discovery of molecular glues

Beyond the specific example of ENL, the study published in Nature Chemical Biology demonstrates a broadly applicable discovery strategy. By combining high-throughput chemistry with functional screening in cells, the researchers show how the identification of molecular glues can be transformed from a serendipitous process into a systematic workflow.

“Our goal is to make proximity-inducing drugs discoverable in a rational and scalable way,” says Winter. “In the long term, this could open up entirely new therapeutic opportunities for proteins that were previously considered undruggable.”

The Study “High-throughput ligand diversification to discover chemical inducers of proximity” was published in Nature Chemical Biology on 16 February 2026. DOI: 10.1038/s41589-025-02137-2

Authors: James B. Shaum, Miquel Muñoz i Ordoño, Erica A. Steen, Daniela V. Wenge, Hakyung Cheong, Jordan Janowski, Moritz Hunkeler, Eric M. Bilotta, Zoe Rutter, Paige A. Barta, Abby M. Thornhill, Natalia Milosevich, Lauren M. Hargis, Timothy R. Bishop, Trever R. Carter, Bryce da Camara, Matthias Hinterndorfer, Lucas Dada, Wen-Ji He, Fabian Offensperger, Hirotake Furihata, Sydney R. Schweber, Charlie Hatton, Yanhe (Crane) Wen, Benjamin F. Cravatt, Keary M. Engle, Katherine A. Donovan, Bruno Melillo, Seiya Kitamura, Alessio Ciulli, Scott A. Armstrong, Eric S. Fischer, Georg E. Winter, Michael A. Erb.

Funding: This study was supported by the Austrian Academy of Sciences, as well as by the European Research Council (ERC), the Austrian Science Fund (FWF), and the Vienna Science and Technology Fund (WWTF). Additional support was provided by the Innovative Medicines Initiative 2 Joint Undertaking (EUbOPEN), the Ono Pharma Foundation, the Baxter Foundation, the Boehringer Ingelheim Fonds, the Boehringer Ingelheim Stiftung, the German Research Foundation (DFG), the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF).

Download: Press Release CeMM-AITHYRA